View this resource

as a PDF >>

**********

View this resource

in Arabic

**********

View this resource

in Chinese

**********

View this resource

in Dutch

**********

View this resource

in French

**********

View this resource

in Spanish

Climate change has caused grievous damage to the Earth and all living beings. As we become more and more aware of this damage, and the inadequate human response to it, we are left with a range of feelings. We may feel discouraged by our national governments’ limited response in the face of the magnitude of climate change. We may feel powerless and exhausted because so many people appear uninformed or even unconcerned about the climate emergency. We may feel overwhelmed by bleak scientific reports—for example, about rapidly melting ice—and by news of catastrophic weather events. Many young people are losing hope for their future, wondering if it makes sense to start families and bring babies into a world on the brink of disaster. So many of us feel rage, despair, and deep grief.

It is still possible to limit the effects of human-caused catastrophic climate change and restore the environment. Most of us want to make a bigger difference. We want to prevent additional damage and reverse as many existing impacts as we can. Scientists want to galvanize the scientific community and more effectively inform the public. Activists want to engage growing numbers of people in the movement to address climate change. Young people want to regain hope and be confident they have a future. Educators want to develop better strategies for teaching about the climate emergency. All of us want to increase our capacity to effectively address climate change now. At the same time, feelings of rage, fear, and grief have interfered with our thinking well about what can be done.

NOTICING THE FEELINGS

Experts are noticing how the increasing visibility of climate change affects mental health. It is being called “climate grief”—depression, anxiety, and mourning over climate change. The American Psychological Association’s report on emotional trauma from climate change says that more people are feeling “a number of different emotions, including fear, anger, feelings of powerlessness, or exhaustion.” Joëlle Gergis, award winning Australian scientist, describes the “volcanic rage” that she experiences in the face of climate change. She says that “I catch myself unexpectedly weeping . . . what surfaces is pure grief.” Gergis acknowledges that she needs to “thaw the emotionally frozen parts” of herself to effectively address climate change. Searching for “climate grief” or “climate anxiety” online yields increasing numbers of stories on the emotional toll of climate change and the importance of addressing its impact on our emotional well-being.

CONSEQUENCES OF FAILURE TO HEAL THE EMOTIONAL HARM

Unreleased, pent-up feelings can harm humans in many ways. Unhealed grief, fear, and frustration tend to interrupt our initiative and dim our hope for the future. Unreleased painful feelings can drain our energy and interfere with our ability to bring our full intelligence to bear on the world around us. Emotional hurts interfere with thinking well about what is to be done and acting appropriately and effectively—in this case, to end environmental degradation.

Many of us attempt to ignore such feelings—as something to push aside, and we act as though

they don’t matter. But doing this can leave us discouraged and despairing. Unless we heal the emotional harm, it can be hard to stay motivated. It can be hard to stay focused on addressing the climate crisis.

Some people attempt to use their grief and rage to fuel their climate change work. This is akin to using jet fuel in a petrol car. There will be misfiring, a smoking engine, and eventually the engine will burn. Major repair will be needed to get it going again.

We need opportunities to openly grieve about the damage being done to the Earth. Doing this can release enormous energy and free our thinking. Healing climate grief can give us the energy and ambition we need to respond appropriately to the climate emergency.

TTHE IMPORTANCE OF HEALING EMOTIONAL HARM

We are organizing ourselves and the people around us to make the necessary changes— but doing this is more difficult in the face of unhealed climate grief. Scientists and people from all walks of life and all strata of society need to “un-numb” as we face the devastating news about damage from climate change. We need to create supportive environments where we can “thaw out” the feelings that come up and release them. Only then can we most appropriately and effectively respond to the climate crisis.

In addition to the climate grief impacting us, we experience emotional harm from oppression and other hurtful experiences. This interferes with our ability to think clearly and sets groups of people against each other. This makes it difficult for us to think about and respond effectively to the climate emergency. It makes working together in broad coalitions more difficult and slows us down.

Healing from the hurts that help to hold oppression in place and lead to other harmful behavior is neither quick nor easy work. Many of us resist this personal healing work. We may have survived by numbing ourselves to the harm done to us by oppression. Some of us assume that we will never be free of this harm.

HOW WE DO THIS

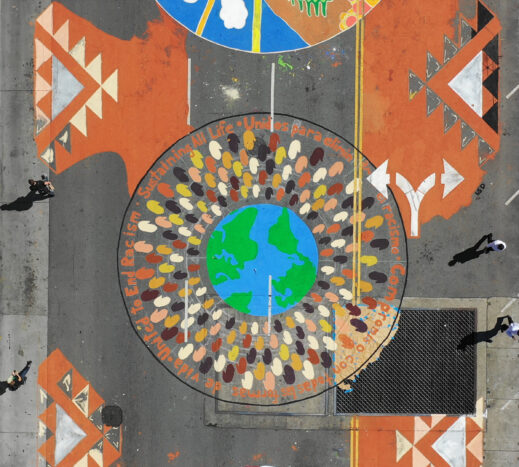

In Sustaining All Life and United to End Racism we have learned that it is possible to free ourselves from these hurts and address barriers to effective organizing. We have some tools that have been effective in healing from climate grief, that have increased people’s courage, initiative, and energy for doing climate change work.

We can heal from hurtful experiences if someone listens to us attentively and allows and encourages us to release the grief, fear, and other painful emotions. This happens by means of our natural healing processes—talking, crying, trembling, expressing anger, and laughing. By releasing emotional pain in a supportive network, we can stay united, hopeful, thoughtful, joyful, and committed. This in turn strengthens us in building our movements to stop the effects of climate change and racism.

The healing work occurs best in a network of people who support each other to notice, share, and release feelings of climate grief. The easily accessible healing process takes place in a safely structured setting. People become skillful at using it.

Our tools include information about how to create networks that can support ongoing work to heal climate grief. The tools can be shared with our home communities and organizations.